Before we dive into a healthy diet, weight-loss goals, or even a full fast, there is an enemy in our way.

A demon that, even if we overcome it for a time, is so deeply ingrained into our needs, it follows us throughout life, guides our steps and at every chance reminds us of its existence. If you are interested to know what this demon is, how it works and what it does, then silence that stomach-growl and buckle up for another nosy exploration into the world of…

Hunger

What is hunger

Hunger is a drive as old as life. This most fundamental want guides microorganisms as it does mammals and all the other slaves of thermodynamic’s second law. For most of our existence it has been a steady companion until progress, armed with domestication of animals, farming, and one or another technical revolution, put a big damper on it.

Nowadays, most (sadly, not all [Burki 2022]) of humanity doesn’t have to experience the hunger of famines. For us privileged it is an occasional feeling of discomfort, not a gut wrenching fight for existence.

How hunger works

For a long time, it was thought that the stomach was responsible for the sense of emptiness. Stomach growls are after all a pretty audible indicator.

Then scientists discovered the real culprit behind hunger and like so many mechanisms in our bodies it is caused by a hormone with the fitting name ghrelin [Nakazato 2001, Cummings 2004]. Although in reality hunger is a complicated thing, the hormone is a major motivator to consume anything that lands on our plates.

But ghrelin isn’t released when our stomaches start to sing their song of emptiness. Instead the key for the hormone’s release lies in our blood and habits.

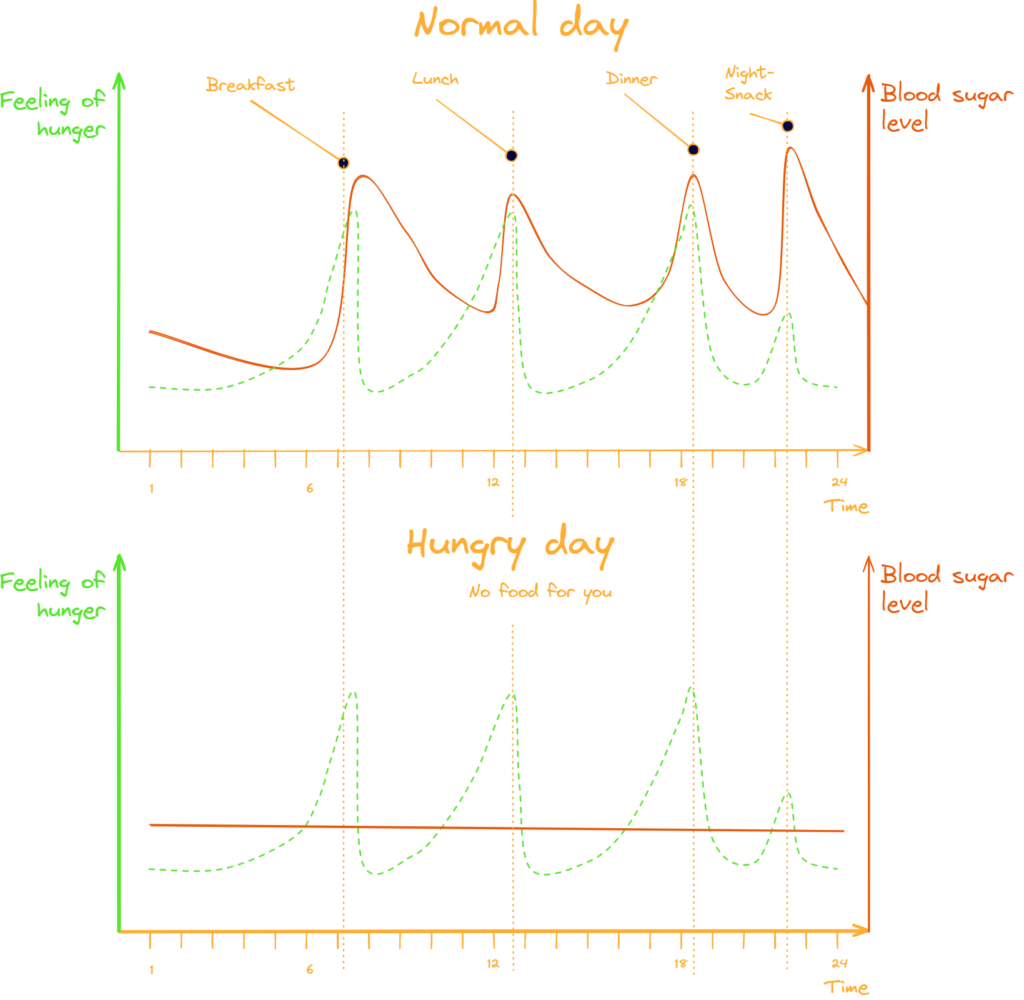

For one, ghrelin-levels rise when the glucose content in our blood falls below certain limits [Tschop 2000]. But evolution being what evolution is, it wasn’t content with this simple control-mechanism in best if-then style.

It might have been a bit of a conundrum because researchers saw that ghrelin-levels seemed to rise at certain times for no apparent reason whatsoever, but calm again like happy puppies even when the test subjects didn’t have their meal [Cummings 2001].

It didn’t take long though until the scientists realized that ghrelin is also released at the expectation of food [Cummings 2001, Drazen 2006]. In that way, ghrelin does control our regular feeding times and prepares our body for the whole ingestion-process [Hosoda 2022].

Anyone who ever had a cat or dog knows that no alarm clock can compete with that punctuality. Our chief paw officer can get quite demanding when her plate isn’t ready at the same time it was the previous day.

What does hunger

Once ghrelin gets released a whole dance of steps starts to play out. The most important one being the binding of ghrelin to the growth hormone secretagogue receptor with the endearing pet name of GHS-R [Kojima 2001, Sun 2004].

As the GHS-R’s name implies, there is growth involved there. Infact, through its binding ghrelin activates the whole so called growth hormone and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-axis [Sugiyama 2012]. The consequence is of course that human growth hormone levels go up double, triple and more its normal levels when we are hungry, which in turn promotes muscle growth [Schwarz 2000, Nakazato 2001, Salgin 2012, Hosoda 2022]. But ghrelin doesn’t stop with muscle-growth.

Ghrelin-receivers (GHS-R) are present in many areas of the body:

- The brain (pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and hippocampus) [Guan 1997, Hosoda 2022]

- The heart and vascular system [Papotti 2000]

- The human saphenous vein, coronary arteries, left ventricle, and right atrium [Katugampola 2000]

And as such ghrelin has more positive effects than a mental health care professional on a college campus:

- Improved sleep [Weikel 2003]

- Reduced inflammation [Hosoda 2022]

- Enhanced vascular activity [Hosoda 2022]

- Reduced heart failure [Hosoda 2022]

- Reduced arrhythmias [Hosoda 2022]

- Neurogenesis and improved learning and memory [Fontan-Lozano 2007, Li 2013, Singh 2012]

But why?

But why would a body that feels hungry and therefore knows that it might go through tough times make such investments that will cost it even more energy?

As we pointed out in the “Intro to Fasting”-article extended periods of time without food are the daily grind of the wild [MacNulty 2014]. The shift to other energy sources such as impressively stored fat is only one part of the whole survival-phase our bodies typically go through [Walker 2010]. The other part is the retention and ideal use of all the means the body has available to acquire food.

Muscles shouldn’t therefore stand on our cells menu for the day that otherwise has cool sounding mechanisms on it such as gluconeogenesis or autophagy to deal with low food availability.

And the same applies to our ability to solve problems.

A smart hunter-gatherer is a successful hunter-gatherer

Outro

It is important to know that all the benefits described above, although great, are the body preparing itself to go into an emergency state that not only borders on the unhealthy but can easily cross into it. Malnutrition is dangerous and prolonged states of fasting have caused injuries and death [Harrison 1966, Hermann 1968, Ross 1969, Rooth 1970, Munro 1972, British Medical Journal 1978, Devathasan 1982, Kerndt 1982, Waterston 1986]

So although feeling hungry, like when we try that new healthy diet or do a fast, is among the more suboptimal states of being, it is worth to suffer through…for a while.

| Key | Citation |

|---|---|

| British Medical Journal 1978 | Fasting and obesity. (1978). British medical journal, 1(6114), 673. |

| Burki 2022 | Burki, T. (2022). Food security and nutrition in the world. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(9), 622. |

| Cummings 2001 | Cummings, D. E., Purnell, J. Q., Frayo, R. S., Schmidova, K., Wisse, B. E., & Weigle, D. S. (2001). A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes, 50(8), 1714-1719. |

| Cummings 2004 | Cummings, D. E., Frayo, R. S., Marmonier, C., Aubert, R., & Chapelot, D. (2004). Plasma ghrelin levels and hunger scores in humans initiating meals voluntarily without time-and food-related cues. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 287(2), E297-E304. |

| Devathasan 1982 | Devathasan, G., & Koh, C. (1982). Wernicke’s encephalopathy in prolonged fasting. The Lancet, 320(8307), 1108-1109.” |

| Drazen 2006 | Drazen, D. L., Vahl, T. P., D’Alessio, D. A., Seeley, R. J., & Woods, S. C. (2006). Effects of a fixed meal pattern on ghrelin secretion: evidence for a learned response independent of nutrient status. Endocrinology, 147(1), 23-30. |

| Fontan-Lozano 2007 | Fontán-Lozano, Á., Sáez-Cassanelli, J. L., Inda, M. C., de los Santos-Arteaga, M., Sierra-Domínguez, S. A., López-Lluch, G., … & Carrión, Á. M. (2007). Caloric restriction increases learning consolidation and facilitates synaptic plasticity through mechanisms dependent on NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(38), 10185-10195. |

| Guan 1997 | Guan, X. M., Yu, H., Palyha, O. C., McKee, K. K., Feighner, S. D., Sirinathsinghji, D. J., … & Howard, A. D. (1997). Distribution of mRNA encoding the growth hormone secretagogue receptor in brain and peripheral tissues. Molecular brain research, 48(1), 23-29. |

| Harrison 1966 | Harrison, M., & Harden, R. (1966). The long-term value of fasting in the treatment of obesity. Lancet, 2, 1340-1342. |

| Hermann 1968 | Hermann, L. S., & Iversen, M. (1968). Death during therapeutic starvation. Lancet, 2. |

| Hosoda 2022 | Hosoda, H. (2022). Effect of Ghrelin on the Cardiovascular System. Biology, 11(8), 1190. |

| Katugampola 2000 | Katugampola, S. D., Pallikaros, Z., & Davenport, A. P. (2001). [125I‐His9]‐Ghrelin, a novel radioligand for localizing GHS orphan receptors in human and rat tissue; up‐regulation of receptors with atherosclerosis. British journal of pharmacology, 134(1), 143-149. |

| Kerndt 1982 | Kerndt, P. R., Naughton, J. L., Driscoll, C. E., & Loxterkamp, D. A. (1982). Fasting: the history, pathophysiology and complications. Western Journal of Medicine, 137(5), 379. |

| Kojima 2001 | Kojima, M., Hosoda, H., Matsuo, H., & Kangawa, K. (2001). Ghrelin: discovery of the natural endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 12(3), 118-122. |

| Li 2013 | Li, L., Wang, Z., & Zuo, Z. (2013). Chronic intermittent fasting improves cognitive functions and brain structures in mice. PloS one, 8(6), e66069. |

| MacNulty 2014 | MacNulty, D. R., Tallian, A., Stahler, D. R., & Smith, D. W. (2014). Influence of group size on the success of wolves hunting bison. PloS one, 9(11), e112884. |

| Munro 1972 | Munro, J. F., & Duncan, L. J. (1972). Fasting in the treatment of obesity. The Practitioner, 208(246), 493-498. |

| Nakazato 2001 | Nakazato, M., Murakami, N., Date, Y., Kojima, M., Matsuo, H., Kangawa, K., & Matsukura, S. (2001). A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature, 409(6817), 194-198. |

| Natalucci 2005 | Natalucci, G., Riedl, S., Gleiss, A., Zidek, T., & Frisch, H. (2005). Spontaneous 24-h ghrelin secretion pattern in fasting subjects: maintenance of a meal-related pattern. European Journal of Endocrinology, 152(6), 845-850. |

| Papotti 2000 | Papotti, M., Ghè, C., Cassoni, P., Catapano, F., Deghenghi, R., Ghigo, E., & Muccioli, G. (2000). Growth hormone secretagogue binding sites in peripheral human tissues. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(10), 3803-3807. |

| Rooth 1970 | Rooth, G., & Carlström, S. (1970). Therapeutic fasting. Acta medica scandinavica, 187(1‐6), 455-463. |

| Ross 1969 | Ross, S. K., Macleod, A., Ireland, J. T., & Thomson, W. S. (1969). Acidosis in obese fasting patients. British Medical Journal, 1(5640), 380. |

| Salgin 2012 | Salgin, B., Marcovecchio, M. L., Hill, N., Dunger, D. B., & Frystyk, J. (2012). The effect of prolonged fasting on levels of growth hormone-binding protein and free growth hormone. Growth Hormone & IGF Research, 22(2), 76-81. |

| Schwarz 2000 | Schwartz, M. W., Woods, S. C., Porte Jr, D., Seeley, R. J., & Baskin, D. G. (2000). Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature, 404(6778), 661-671. |

| Singh 2012 | Singh, R., Lakhanpal, D., Kumar, S., Sharma, S., Kataria, H., Kaur, M., & Kaur, G. (2012). Late-onset intermittent fasting dietary restriction as a potential intervention to retard age-associated brain function impairments in male rats. Age, 34, 917-933. |

| Sugiyama 2012 | Sugiyama, M., Yamaki, A., Furuya, M., Inomata, N., Minamitake, Y., Ohsuye, K., & Kangawa, K. (2012). Ghrelin improves body weight loss and skeletal muscle catabolism associated with angiotensin II-induced cachexia in mice. Regulatory peptides, 178(1-3), 21-28. |

| Sun 2004 | Sun, Y., Wang, P., Zheng, H., & Smith, R. G. (2004). Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(13), 4679-4684. |

| Tschop 2000 | Tschop, M., Smiley, D. L., & Heiman, M. L. (2000). Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature, 407(6806), 908-913. |

| Walker 2010 | Walker, A. K., Yang, F., Jiang, K., Ji, J. Y., Watts, J. L., Purushotham, A., … & Näär, A. M. (2010). Conserved role of SIRT1 orthologs in fasting-dependent inhibition of the lipid/cholesterol regulator SREBP. Genes & development, 24(13), 1403-1417. |

| Waterston 1986 | Waterston, J. A., & Gilligan, B. S. (1986). Wernicke’s encephalopathy after prolonged fasting. |

| Weikel 2003 | Weikel, J. C., Wichniak, A., Ising, M., Brunner, H., Friess, E., Held, K., … & Steiger, A. (2003). Ghrelin promotes slow-wave sleep in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 284(2), E407-E415. |

Leave a Reply