Intro

We all feel it and science agrees. More studies than I wanted to read indicate that the average worker spends over 20% of their time in scheduled meetings, and another 20% in impromptu ones [§ Stray 2020, § Mensik 2024]. That’s a mighty two full days per week to sit in a (virtual) room and…listen?

Yes, significant portions if not whole meeting-sessions are about passing information from A to B.

Ask yourself: How many of your professional Get-Togethers were what meetings actually should be about—decision-making, idea generation, conflict resolution, feedback sessions, relationship building in lieu of getting the latest update about someone else’s process?

For a deeper look why we should meet check out the article “Meet with Purpose“.

Alignments aren’t always bad, but they are rarely the best use of time [§ Caimi 2014].

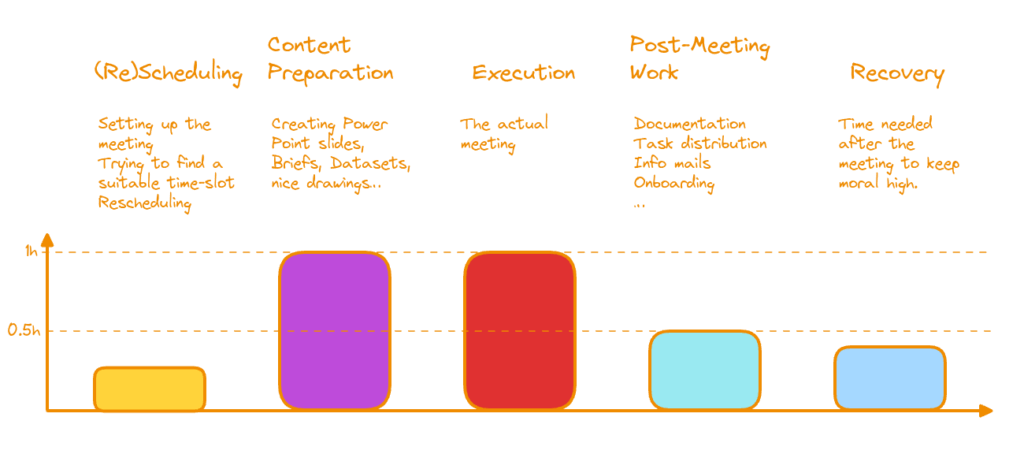

Add to that the true cost of meetings and it becomes quite obvious that instead of sending out invites left and right for the smallest update or infinitesimal question, we should take a step back and really optimize the time we get together.

Alignments – The Bane of Productivity

Defining Alignments

An alignment meeting is a session where a group gathers to:

- hear the same update

- get looped in

- be “on the same page”

It often includes:

- PowerPoint slides

- passive information transfer

- little discussion, even less decision-making

In short, it is the meeting version of forwarding an email to ten people with an “FYI” content or a simple question.

The Alignment Issue

Alignment meetings might feel productive—we sit in a room, listen, use energy—but they rarely are.

Alignments scale poorly.

Alignments live of the amount of meeting participants. The more people are listening, the better—for the alignment. But every invitee increases the cost, easily by 3 times the alignment length.

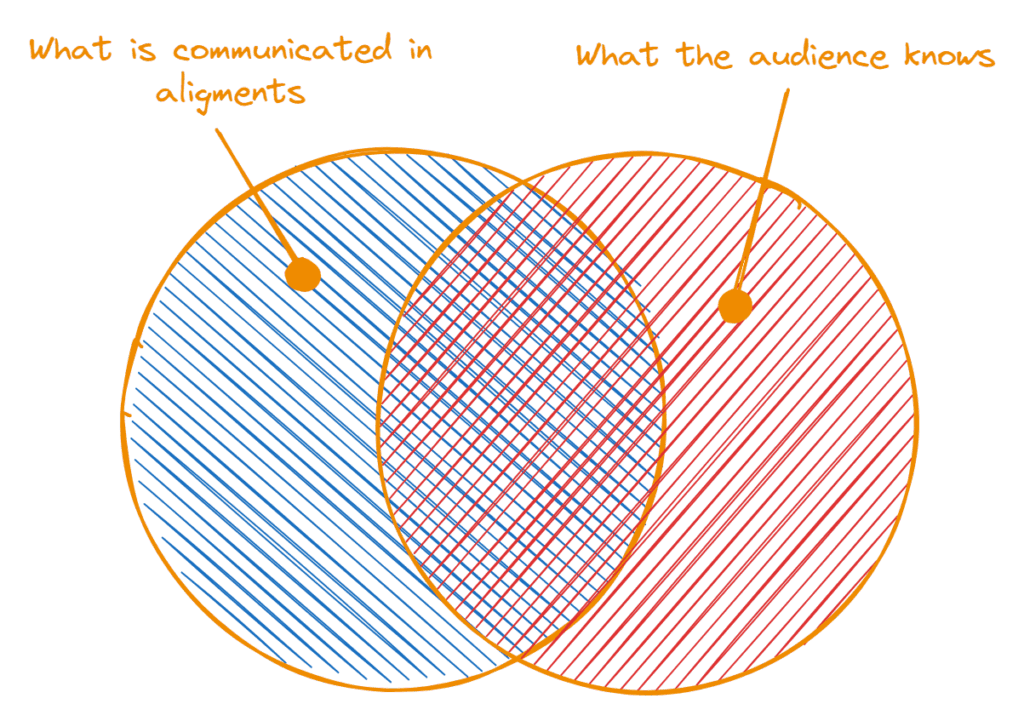

Alignments suffer from TMI.

They often mix stakeholders with different needs for depth of context, creating unnecessary noise and “Too Much Information”.

Alignments suffer from information redundancy.

In addition, participants might often know large parts of the alignment, leading to information redundancy.

That way alignments can easily be wasted time for the audience while they sit through it and consume the content at content at the same slow pace, even when some already understand it or could have skimmed a memo in half the time.

In general, alignments often repackage what’s already available in dashboards, documentation, or progress updates — just in meeting form.

Alignments promote passive participation.

Most participants in alignments are listeners, not contributors. Sadly, only a minority of presenters stir the engagement of Huberman or have that same podcaster charisma.

Engagement dies, minds drift and other important tasks come into focus.

I can’t remember the first time I witnessed a colleague answering mails during a meeting, but I do remember the first time I started working on something else during a large scale alignment.

For a good amount of coworkers, myself included, it became almost the only way to deal with the increasing amount of meetings while still getting work done and

- …write that quick mail.

- …answer a message.

- …finish that last graphic or spreadsheet.

If only there would be no downside to such multi taskery, but there is. The efficiency of the alignment falls through and we could have just as well skipped the whole meeting.

Ironically organizations that rely on alignments the most might therefore get the least value out of them. The consequence is that in such environments, (project) managers are forced to set up even more alignments to assure all team members have the right information, fueling the whole meeting-machine even further.

And to add insult to injury the information transfer of alignments is often also less effective than alternatives.

When people listen and read slides at the same time, they retain less—this is known as the redundancy effect. Passive listening simply isn’t effective learning [§ Kalyga 2004].

Alignments are often an asynchronous misfit.

Alignments force people to sync at a specific moment, even if they don’t need the information right then (asynchronous misfit).

Alignments blur responsibility

Group alignment can lead to diffusion of responsibility — “everyone heard it” becomes “no one owns it.”

Foundational experiments show that larger group presence diminishes individual likelihood to act — directly paralleling how alignment meetings reduce personal ownership and action [§ Darley 1968].

Alignments discourage documentation.

Unless rigorously documented (and often they aren’t), verbal alignments vanish. People forget, misremember, or need to be re-aligned [§ Newport 2016].

It is one of the reasons why I introduced the rule:

If it isn’t written down, it doesn’t count.

I would even go so far to point out that Alignment meetings are a failure of documentation culture.

When are Alignments useful

Despite all their flaws, alignments do have a place:

- Project kickoffs

- Early-stage collaboration

- High-speed, high-change environments (e.g. startups)

In such environments alignments are a useful tool to asure the team works on the same level of information.

Research also shows that shared mental models and “team cognition” improve coordination — especially in dynamic settings [§ Marks 2001].

Brief, intentional alignment sessions can help build shared context, but they should be used sparingly and purposefully.

How to solve Alignments

Alignments can be solved. The goal is to eliminate them or to reduce them as much as possible.

Documentation

Documentation and their systems can be an effective tool to deal with alignments. In fact, a strong documentation system makes most alignment meetings obsolete. When relevant information is:

- accessible

- up to date

- clearly written

you don’t need to gather everyone to say it out loud.

That of course requires that every person uses the documentation system [§ Newport 2016].

If you want to learn more about the beautiful power tool that is documentation, look into its Higher Order Note.

Pre Brief

Another alternative to Alignments is the Pre Brief. This tool is a document (e.g. PDF, mail, word file, piece of paper, presentation, video) that is given to all participants in preparation for the meeting. It holds all necessary information and gives the participants the base-knowledge for whatever the meeting requires.

If done right, it can eliminate the alignment portion of a meeting entirely or reduce it significantly.

For it to work, like with documentation, the shown information has to stand on its own without any additional necessary explanation.

Amazon 6 Page Memo

According to some sources, Amazon is a user of one form of Pre Briefs in the form of the so called 6 Page Memo.

All Amazon meetings begin with silent reading of the 6-page memo, ensuring attendees are informed before discussion starts.

The result being that everyone starts a meeting with context and jump right into discussions or whatever else the sync entails [§ Carson 2025, § Kantor 2019].

Outro

We don’t just have too many meetings. We have too many alignment meetings — slow, redundant, and often pointless.

These meetings often disguise themselves as collaboration, but at their core, they are synchronous, one-sided information transfers. They monopolize time, diffuse responsibility, and substitute presence for clarity.

Documentation and Pre Briefs can be effective methods to tame this kind of meeting-monster. They either eliminate the need for it entirely or at the very least reduce it significantly.

The goal of course is to create an environment where streamlined work without interruptions is possible.

Let your teams work asynchronously and Meet with Purpose because collaboration shouldn’t require a roomful of passive listeners. It should start with clarity — and end in action.

Sources

| Key | Citation |

|---|---|

| § Allen 2023 | Allen, J. A., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2023). The key features of workplace meetings: Conceptualizing the why, how, and what of meetings at work. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(4), 355-378. |

| § Caimi 2014 | Caimi, G. (2014). Your scarcest resource. Harvard Business Review, 74-80. |

| § Carson 2025 | Carson, E. (2025, July 10). Former Amazon engineer reveals the surprising way Jeff Bezos ran meetings. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-engineer-6-page-memos-reading-culture-jeff-bezos-2025-7 |

| § Darley 1968 | Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: diffusion of responsibility. Journal of personality and social psychology, 8(4p1), 377. |

| § Drucker 1967 | Drucker, P. The Effective Executive (178 pages, 1967). |

| § Kalyga 2004 | Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2004). When redundant on-screen text in multimedia technical instruction can interfere with learning. Human factors, 46(3), 567-581. |

| § Kantor 2019 | Kantor, J. (2019, October 21). Is Amazon unstoppable? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/10/21/is-amazon-unstoppable |

| § Marks 2001 | Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of management review, 26(3), 356-376. |

| § Mensik 2024 | Menšík, H. (2024, June 20). The true cost of meetings, by the numbers. WorkLife. https://www.worklife.news/culture/the-true-cost-of-meetings-by-the-numbers/ |

| § Newport 2016 | Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Hachette UK. |

| § Stray 2020 | Stray, V., & Moe, N. B. (2020). Understanding coordination in global software engineering: A mixed-methods study on the use of meetings and Slack. Journal of Systems and Software, 170, 110717. |

| § Wang 2024 | Wang, R., Qiu, L., Cranshaw, J., & Zhang, A. X. (2024). Meeting Bridges: Designing Information Artifacts that Bridge from Synchronous Meetings to Asynchronous Collaboration. arXiv Preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.03259 |

Leave a Reply