Intro

Pang. Pang! PANG!!!!

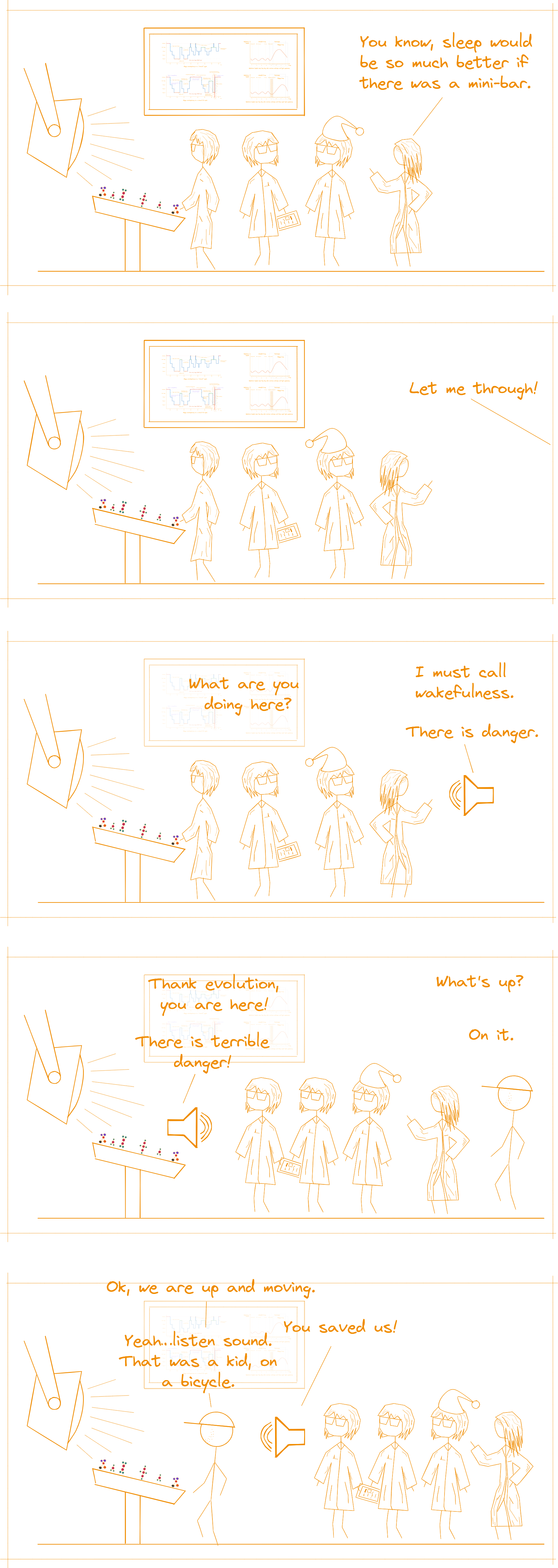

You wake up. “What…!?”, springs to your mind. A mind, that still clings to the dream it so comfortably enveloped you with mere moments ago.

Only after a while do you realize that the rude awakening wasn’t the attempt on your life the evolutionary wiring in your hind-brain believed it was, but just some kids outside. Sighing you drift back down and soon to sleep. No intrinsic thoughts to keep you awake this time. But the night is all but relaxing.

REMS-cycles are interrupted, you jump in and out of NREMS stage 2s like a granny trying to fiddle a thread into a needle, and the next day you feel about as wakeful as a kitty after a night out.

If the scenario above is one of your life’s charming realities, then look no further, close the windows, put in some ear-plugs and follow us on this nosy look into the buzzing world of…

Noise and sleep

A world of noise and its effects

Noise is everywhere. It is carried by the blowing wind, thunders over the horizon during a storm, hums in the wake of every car, plane or train, and reaches your ears through the familiar words of friends and family. Neither humanity, nor you, nor I would be the same without it, but besides being helpful some and annoying at other times, it has another important effect:

Noise reduces our sleep quality

[Matsumoto 2017]

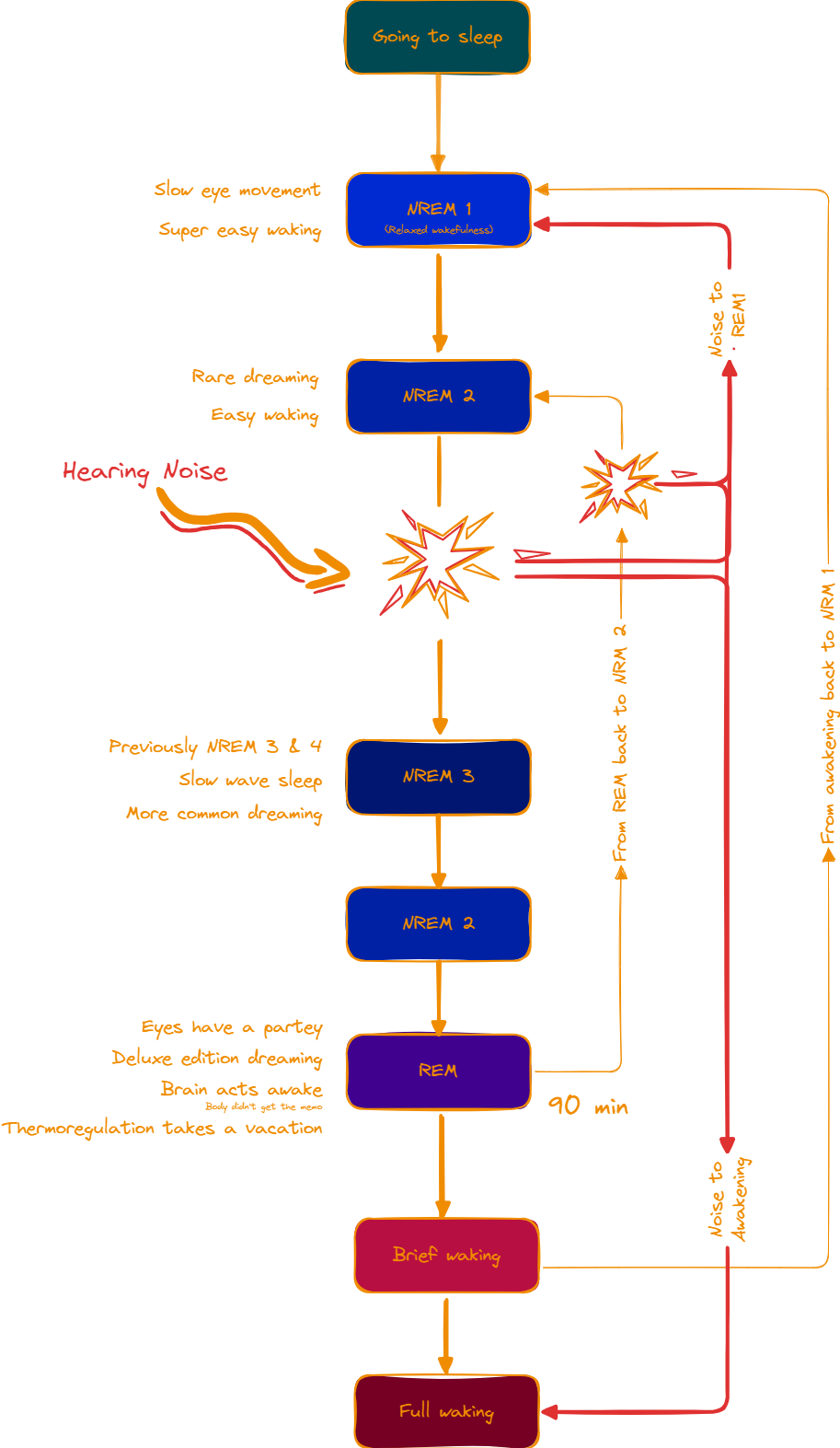

During sleep onset (NREMS stage 1), noise hinders the all so important transition to stage 2 and with it, reaching the oh so more important deeper sleep stages. It can even go so far to take you back from stage 2 to stage 1 [Kawada 1995].

But if that wouldn’t be enough, noise affects also the deeper sleep stages. Like a vicious beast it cuts into our REMS and rips out important parts [Kawada 1999].

Worse, noise can disrupt sleep to the fullest extend. Like a candidates during a tv debate it will roll over any and all carefully operating sleep stage, call upon wakefullness and rise the body from even the deepest slumber [Caddick 2018, Matsumoto 2017, WHO-Europe 2009].

The culprit is in our hindbrain the ascending reticular activating system, a remnant of easier times, without calendars, meetings and continous phone-calls. Sadly, back when the neuronal pathways were created, the designers didn’t consider noise machines sich as cars, planes or televisions and put in a simple “if noise than wake”-switch.

Ok, not that simple.

The rules of noise

Science recommends to keep noise-levels below 30 – 40dBA (think the humming of a fridge) for a typical sleeper to keep the wake-switch from turning [WHO-Europe 2009]. There are some variations from person to person, but the core rule remains:

Humans should sleep in an environment as calm and quiet as possible.

[Bruck 2009, Kawada 1995, Kawada 1999, Marks 2007, Muzet 2007, Nakagawa 1986, Rechtschaffen 1966, Scott 1972, Stanchina 2005, Williams 1964]

Additions

If a quiet environment is not possible, there are some additions to the “rule of noise” that you should consider.

Because evolution only designs complicated switches.

Noise frequency

It has been found that besides the noise itself, its frequency also impacts sleep quality and -duration, with more frequent pulses causing more sleep disruption [Nakagawa 1986].

Single roar less bad than multiple roar, got it.

Noise continuity

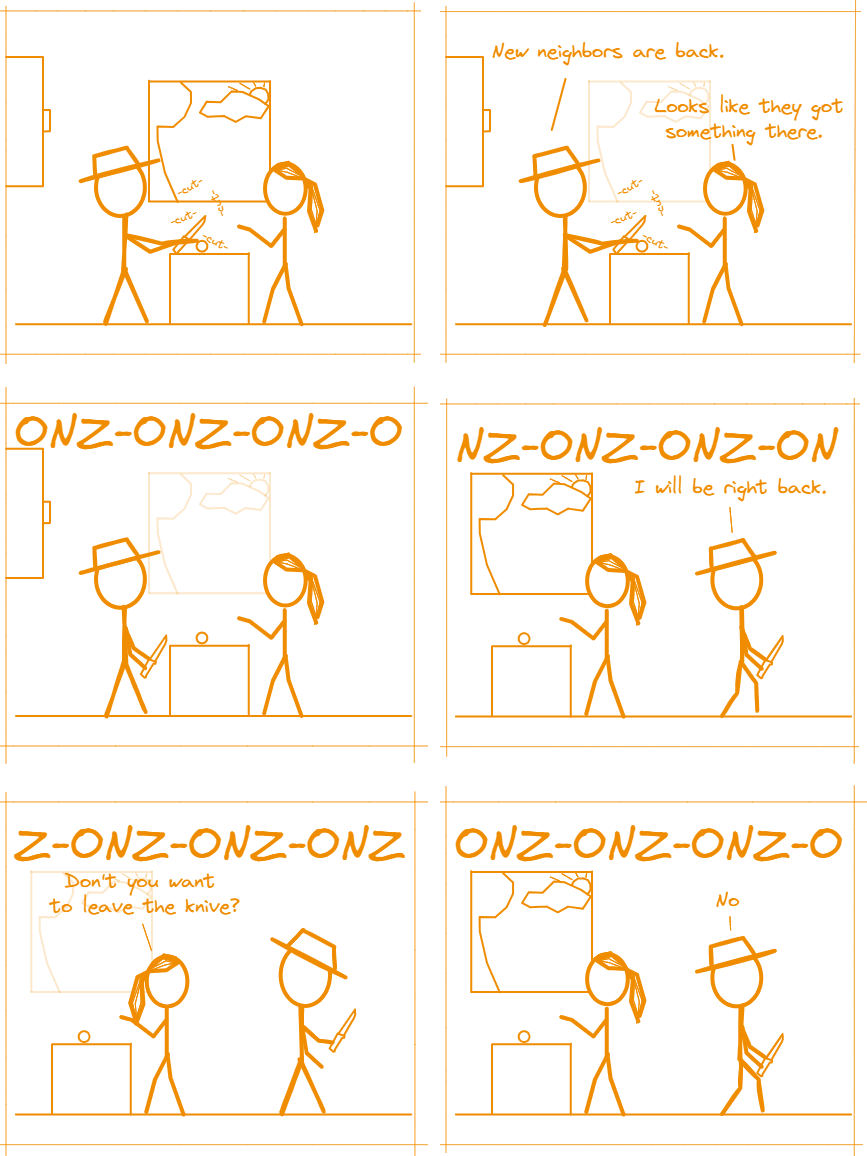

That of course changes if the noise becomes a part of the environment. If car sounds are just part of the background, another car won’t make much of a dent into your sleep curve. That changes of course if the noise is sudden and unexpected [Caddick 2018].

E.g. thunder cracking and signaling the arrival of this week’s fire-delivery.

The city-scape is noisy enough

Still, normal city noise remains to be enough to disturb sleep [Basner 2008, Basner 2011, Bodin 2015, Brink 2011, Pirrera 2014, Popp 2015, Renterghem 2012, Saremi 2008, Stosic 2009, Vos 2013].

Dealing with noise

Living in a calm environment

The first and by all accounts best method to deal with noise is of course to eliminate it.

But before you jump up and realize all those wakeful dreams you had when your neighbor starts to turn up the subwoofer in the middle of the night, consider a more peaceful solution.

Countryside

As we pointed out, although the city is great live in as a human, it is not an ideal place to sleep.

The coutryside, with its trees, hills and wide fields shines with a clear absence of roudy car riders, trains, or similar disturbances, typically.

Insulated room

When you don’t have the option to relocate to calmer places, there is always insulation.

In a time of one record summer after another most people think about energy when insulation is mentioned. Noise-insulation is thermal-insulation’s younger and often overlooked sibling, but at least as if not more important for ones mind and body.

Moving spaces

Moving the bedroom away from the source can already be enough to achieve sufficient insulation [Caddick 2018].

Asking for the consideration of others

Also asking kids, family, friends, relations or servantswe don’t judge to keep their activities civil and quiet while you (try to) sleep can be a great help. Ground rules like “sleeping time-windows” or “night-rest”, during which the sleepers shouldn’t be disturbed or called for can greatly improve sleep quality. And of course sleeping undisturbed tends to be easier when you synchronize your sleeping times with the environment and don’t try to do it while the workers outaide cut open the street [Kuwano 1998, Kuwano 2002, Oswald 1960, Sasazawa 2006].

Modifying oneself

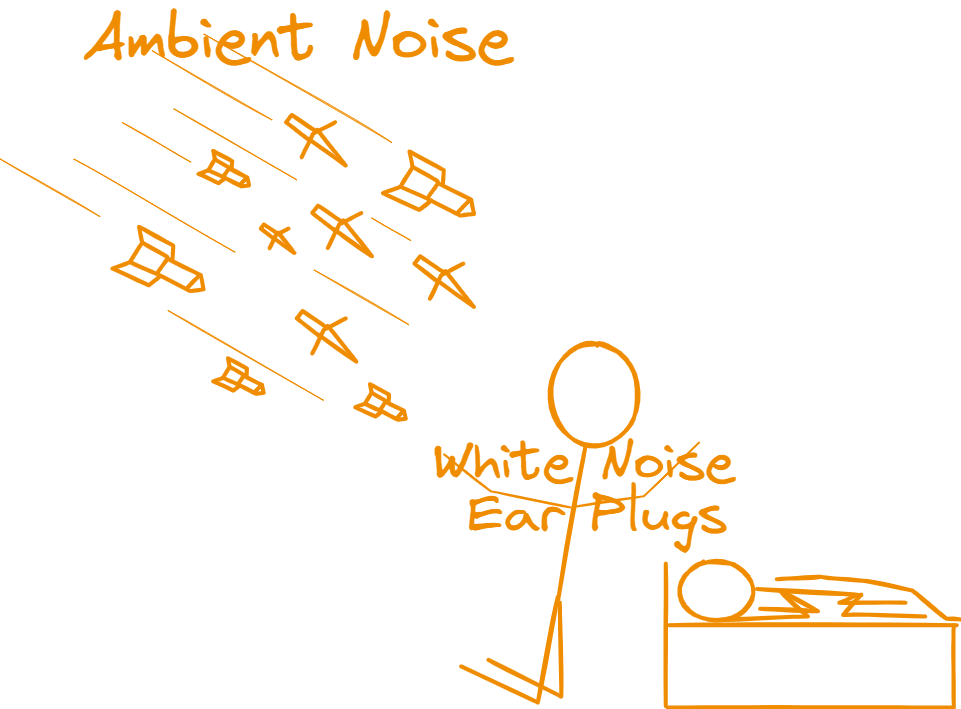

White noise

With the invention of fans and the blissful stream of air during a hot night came another devine side effect. As it turns out, white noise from fans and other sources, protects sleep by masking the influence of exposure to other intermittent noises. If you try this method, aim for a continuous noise of 62 dB containing a blend of 1-22.05 kHz [Stanchina 2005].

Ear plugs

Then there are more direct matters, one of which I regularly apply myself: Ear-plugs. Science found that ear-plugs can be a bullwark that protects the sleeping [Jones 2012, Wallace 1999]. A result that I can wholeheartedly support.

Sleeping next to my nosy companion, and our tapsy chief paw officer these little gems are a god-send in the sound-volatile environment of our bedroom.

Get used to it

And last, there is the simple mechanism of conditioning. Humans can get used to a great many deal of things, even noise [Bonnet 1989, McGuire 2016]. Nevertheless, you shouldn’t only rely on your body and its willingness to shift your auditory arousal threshold. Evolution has a thing for stability and a few nights or even weeks of noise won’t drastically change your ability to overhear the sound of the concrete jungle.

Outro

So as you see, noise is a chief disrupter in the universe of sleep and should be banished to the shadow realm. Try to apply some of the methods from the article if you fall victim to such auditory disturbances and feel free to share your own.

Always remember…

Quiet and calm makes for good sleeping-form.

Sources

| Key | Citation |

|---|---|

| Basner 2008 | Basner, M., Glatz, C., Griefahn, B., Penzel, T., & Samel, A. (2008). Aircraft noise: effects on macro-and microstructure of sleep. Sleep medicine, 9(4), 382-387. |

| Basner 2011 | Basner, M., Müller, U., & Elmenhorst, E. M. (2011). Single and combined effects of air, road, and rail traffic noise on sleep and recuperation. Sleep, 34(1), 11-23. |

| Bodin 2015 | Bodin, T., Björk, J., Ardö, J., & Albin, M. (2015). Annoyance, sleep and concentration problems due to combined traffic noise and the benefit of quiet side. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(2), 1612-1628. |

| Bonnet 1989 | Bonnet, M. H. (1989). Infrequent periodic sleep disruption: effects on sleep, performance and mood. Physiology & Behavior, 45(5), 1049-1055. |

| Brink 2011 | Brink, M., Omlin, S., Müller, C., Pieren, R., & Basner, M. (2011). An event-related analysis of awakening reactions due to nocturnal church bell noise. Science of the total environment, 409(24), 5210-5220. |

| Bruck 2009 | Bruck, D., Ball, M., Thomas, I., & Rouillard, V. (2009). How does the pitch and pattern of a signal affect auditory arousal thresholds?. Journal of sleep research, 18(2), 196-203. |

| Caddick 2018 | Caddick, Z. A., Gregory, K., Arsintescu, L., & Flynn-Evans, E. E. (2018). A review of the environmental parameters necessary for an optimal sleep environment. Building and environment, 132, 11-20. |

| Jones 2012 | Jones, C., & Dawson, D. (2012). Eye masks and earplugs improve patient’s perception of sleep. Nursing in critical care, 17(5), 247-254. |

| Kawada 1995 | Kawada, T., & Suzuki, S. (1995). Instantaneous change in sleep stage with noise of a passing truck. Perceptual and motor skills, 80(3), 1031-1040. |

| Kawada 1999 | Kawada, T., & Suzuki, S. (1999). Change in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in response to exposure to all-night noise and transient noise. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal, 54(5), 336-340. |

| Kuwano 1998 | Kuwano, S. (1998). The effect of noise on the effort to sleep. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Noise Control Engineering, 1998. |

| Kuwano 2002 | Kuwano, S., Mizunami, T., Namba, S., & Morinaga, M. (2002). The effect of different kinds of noise on the quality of sleep under the controlled conditions. Journal of sound and vibration, 250(1), 83-90. |

| Marks 2007 | Marks, A., & Griefahn, B. (2007). Associations between noise sensitivity and sleep, subjectively evaluated sleep quality, annoyance, and performance after exposure to nocturnal traffic noise. Noise and Health, 9(34), 1-7. |

| Matsumoto 2017 | Matsumoto, Y., Uchimura, N., Ishida, T., Morimatsu, Y., Mori, M., Inoue, M., … & Ishitake, T. (2017). The relationship of sleep complaints risk factors with sleep phase, quality, and quantity in Japanese workers. Sleep and biological rhythms, 15, 291-297. |

| McGuire 2016 | McGuire, S., Müller, U., Elmenhorst, E. M., & Basner, M. (2016). Inter-individual differences in the effects of aircraft noise on sleep fragmentation. Sleep, 39(5), 1107-1110. |

| Muzet 2007 | Muzet, A. (2007). Environmental noise, sleep and health. Sleep medicine reviews, 11(2), 135-142. |

| Nakagawa 1986 | Nakagawa, Y. (1986). Sleep disturbances due to exposure to tone pulses throughout the night. Sleep, 10(5), 463-472. |

| Oswald 1960 | Oswald, I. A. N., Taylor, A. M., & Treisman, M. (1960). Discriminative responses to stimulation during human sleep. Brain: a journal of neurology. |

| Pirrera 2014 | Pirrera, S., De Valck, E., & Cluydts, R. (2014). Field study on the impact of nocturnal road traffic noise on sleep: The importance of in-and outdoor noise assessment, the bedroom location and nighttime noise disturbances. Science of the Total Environment, 500, 84-90. |

| Popp 2015 | Popp, R. F., Maier, S., Rothe, S., Zulley, J., Crönlein, T., Wetter, T. C., … & Hajak, G. (2015). Impact of overnight traffic noise on sleep quality, sleepiness, and vigilant attention in long-haul truck drivers: results of a pilot study. Noise and health, 17(79), 387-393. |

| Rechtschaffen 1966 | Rechtschaffen, A., Hauri, P., & Zeitlin, M. (1966). Auditory awakening thresholds in REM and NREM sleep stages. Perceptual and motor skills, 22(3), 927-942. |

| Renterghem 2012 | Renterghem, T. V., & Botteldooren, D. (2012). Focused study on the quiet side effect in dwellings highly exposed to road traffic noise. International journal of environmental research and public health, 9(12), 4292-4310. |

| Saremi 2008 | Saremi, M., Grenèche, J., Bonnefond, A., Rohmer, O., Eschenlauer, A., & Tassi, P. (2008). Effects of nocturnal railway noise on sleep fragmentation in young and middle-aged subjects as a function of type of train and sound level. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 70(3), 184-191. |

| Sasazawa 2006 | Sasazawa, Y., Kawada, T., & Suzuki, S. (2006, December). The relationship between variety of community noise and sleep disturbance in Japanese. In Inter-noise and NOISE-con Congress and Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2006, No. 3, pp. 4205-4213). Institute of Noise Control Engineering. |

| Scott 1972 | Scott, T. D. (1972). The effects of continuous, high intensity, white noise on the human sleep cycle. Psychophysiology, 9(2), 227-232. |

| Stanchina 2005 | Stanchina, M. L., Abu-Hijleh, M., Chaudhry, B. K., Carlisle, C. C., & Millman, R. P. (2005). The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep medicine, 6(5), 423-428. |

| Stosic 2009 | Stosic, L., Belojevic, G., & Milutinovic, S. (2009). Effects of traffic noise on sleep in an urban population. Arhiv za higijenu rada i toksikologiju, 60(3), 335. |

| Vos 2013 | Vos, J., & Houben, M. M. (2013). Enhanced awakening probability of repetitive impulse sounds. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134(3), 2011-2025. |

| Wallace 1999 | Wallace, C. J., Robins, J., Alvord, L. S., & Walker, J. M. (1999). The effect of earplugs on sleep measures during exposure to simulated intensive care unit noise. American Journal of Critical Care, 8(4), 210. |

| WHO-Europe 2009 | Europe, W. H. O. (2009). Night noise guidelines for Europe. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen. |

| Williams 1964 | Williams, H. L., Hammack, J. T., Daly, R. L., Dement, W. C., & Lubin, A. (1964). Responses to auditory stimulation, sleep loss and the EEG stages of sleep. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology. |

Leave a Reply