TLDR: Hunger can effectively be reduced through exercise. It is thereby an effective method to counteract the hunger-hormone ghrelin and to disrupt eating habits.

Imagine you try fasting and lunch-time comes about. Your stomach growls and the urge to peek into the fridge becomes almost overwhelming. Going for a run will probably be the last thing on your wish list in that moment. But in many if not all instances, it is among the best things you can do. Because…

So follow us on this nosy exploration of how…

Exercise affects hunger

The basics

When scientists investigated the eating-habits of exercising folk, like athletes, it turned out that exercise does not only not increase hunger, even at high intensities, but, and imagine this article’s autor’s surprise, can also reduce appetite, more efficiently than a delicious set of cookies on a plate [Thompson 1988, King 1995, King 1996, King 1997, Westerterp-Plantenga 1997, Lluch 1998, Blundell 1999, Vatansever-Ozen 2011].

Uff, I better do some push ups.

Even vigorous (“sweatily screaming for mercy”) exercise has at least temporarily a negative effect on hunger [King 1994, King 1995, Westerterp-Plantenga 1997, Lluch 1998, Bellisle 1999, Tsofliou 2003].

It is a baffling phenomenon and surely has some evolutionary purpose behind it. Feeling hungry and wanting to just snack on a couch might have been detrimental for food finding or hunting purposes, back when our meals were roaming the great savannas.

How does exercise do?

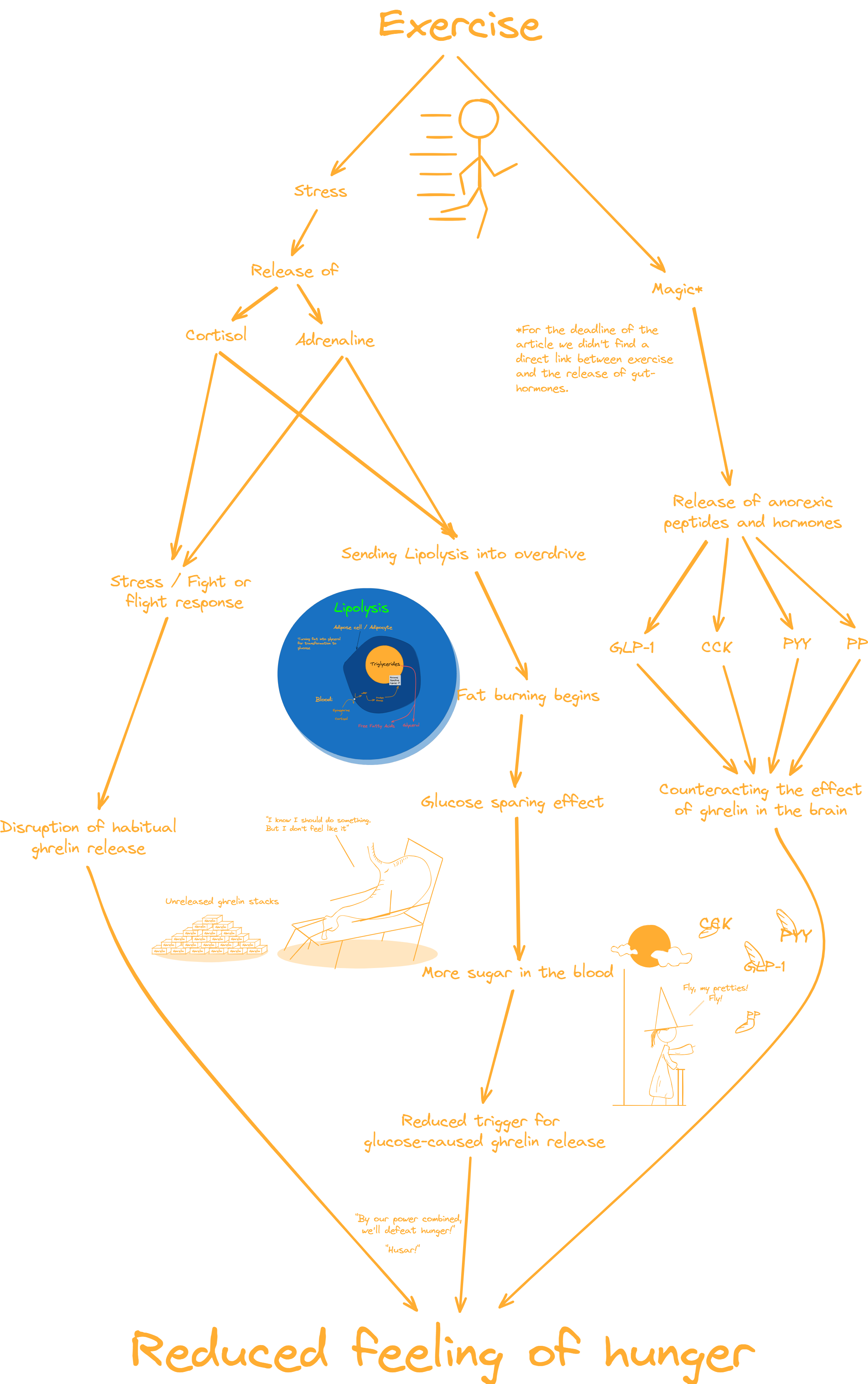

The story of exercise and hunger has 3 parts: One direct, leading us into the labyrinth of the intestines up to the brain, a second of blood and energy and a third of alarms and habits.

A mechanism that bridges the gut to the brain

Exercise makes us sweat, ache and sometimes scream, but did you know that it also builds bridges? In fact, it triggers the release of a whole sack of building blocks in the gut that activate all sorts of spots on the central nervous system. These building blocks, that put any minecraft enthusiast to shame and are excreted by something as simple as a jump up the stairs, are:

- GLP-1 [O’Connor 1995, O’Connor 2006, Martins 2007]

- CCK [Shillabeer 1987, Bailey 2001, Sliwowski 2001]

- PYY [Bartolome 2002, Batterham 2002, Batterham 2003, Martins 2007]

- PP [Hilsted 1980, Sullivan 1984, O’Connor 1995, Sliwowski 2001 ,Martins 2007]

One of the original functions of PYY, CCK and GLP-1 is the inhibition of gastric emptying [Liddle 1995, Liu 1996, Gautier 2008]. It makes sense that we shouldn’t have to worry about potty brakes when we are running for our lives or hunting after our breakfast.

But that is only one of the many effects of these hormones. The other important one is their anorectic properties [Shillabeer 1987, Batterham 2002, Batterham 2003, Gautier 2008]. Translated to the common tongue anorectic means “they reduce appetite” which in turn means:

Exercise triggers the release of gastrointestinal hormones that reduce hunger.

A mechanism of blood and energy

Then there is the second way exercise influences our foody-cravings. This time, we follow the spike of adrenaline that accompanies any good training session …right? Riiiiight!?.

Of course.

Similar to how caffeine affects adrenaline, exercise too can spray it around like an over-enthusiastic firefighter while screaming “Bloody murder!” through our body’s corridors [Sullivan 1984].

The effects of adrenaline on hunger are well documented and show that adrenaline has a strong negative effect on our appetite [Russek 1980]. Similar to how caffeine does it with the glycogen sparing effect, exercise might work similarly due to the activation of fat burning aka. lipolysis [Ryu 2001].

Exercise reduces hunger through the release of adrenaline.

A mechanism of alarms and habits

Have you ever stood in front the fridge, pondering what to eat? Imagine – and we hope you ever only have to imagine such a scenario – that you are suddenly attacked by a huge bird. Food would probably be again the last thing on your mind.

The stress, or fight or flight response our body falls back on when under threat is triggered by our central nervous system, but the message is carried by hormones such as cortisol or again adrenaline [Sullivan 1984, Hill 2008].

Like in large organizations, the majority of our body is blissfully ignorant to events like the comings and goings of giant birds. Which means every time our dear cells sniff the rise of stress hormones they respond accordingly and the only way they know how. Exercise hijacks this response and reduces through the release of stress hormones our baseline food intake [Murphy 2006].

We will take a more in depth look into these kinds of mechanisms with future guides, but can be happy to know that if applied right, this effect can be used to disrupt the habitual hunger trigger.

Exercise reduces hunger through a stress response.

Outro

Especially at medium to high levels, exercise is an effective way to reduce hunger and could be a viable way to overcome the hunger pangs. So instead of heading to out to grab a bite, consider that run.

Sources

| Key | Citation |

|---|---|

| Bailey 2001 | Bailey, D. M., Davies, B., Castell, L. M., Newsholme, E. A., & Calam, J. (2001). Physical exercise and normobaric hypoxia: independent modulators of peripheral cholecystokinin metabolism in man. Journal of Applied Physiology, 90(1), 105-113. |

| Bartolome 2002 | Bartolomé, M. A., Borque, M., Martinez-Sarmiento, J., Aparicio, E., Hernández, C., Cabrerizo, L., & Fernandez-Represa, J. A. (2002). Peptide YY secretion in morbidly obese patients before and after vertical banded gastroplasty. Obesity surgery, 12(3), 324-327. |

| Batterham 2002 | Batterham, R. L., Cowley, M. A., Small, C. J., Herzog, H., Cohen, M. A., Dakin, C. L., … & Bloom, S. R. (2002). Gut hormone PYY3-36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature, 418(6898), 650-654. |

| Batterham 2003 | Batterham, R. L., Cohen, M. A., Ellis, S. M., Le Roux, C. W., Withers, D. J., Frost, G. S., … & Bloom, S. R. (2003). Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3–36. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(10), 941-948. |

| Bellisle 1999 | Bellisle, F. (1999). Food choice, appetite and physical activity. Public health nutrition, 2(3a), 357-361. |

| Blundell 1999 | Blundell, J. E., & King, N. A. (1999). Physical activity and regulation of food intake: current evidence. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 31(11 Suppl), S573-83. |

| Gautier 2008 | Gautier, J. F., Choukem, S. P., & Girard, J. (2008). Physiology of incretins (GIP and GLP-1) and abnormalities in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes & metabolism, 34, S65-S72. |

| Hill 2008 | Hill, E. E., Zack, E., Battaglini, C., Viru, M., Viru, A., & Hackney, A. C. (2008). Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 31, 587-591. |

| Hilsted 1980 | Hilsted, J., Galbo, H., Sonne, B., Schwartz, T., Fahrenkrug, J., de Muckadell, O. B., … & Tronier, B. (1980). Gastroenteropancreatic hormonal changes during exercise. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 239(3), G136-G140. |

| King 1994 | King, N. A., Burley, V. J., & Blundell, J. E. (1994). Exercise-induced suppression of appetite: effects on food intake and implications for energy balance. European journal of clinical nutrition, 48(10), 715-724. |

| King 1995 | King, N. A., & Blundell, J. E. (1995). High-fat foods overcome the energy expenditure induced by high-intensity cycling or running. European journal of clinical nutrition, 49(2), 114-123. |

| King 1996 | King, N. A., Snell, L., Smith, R. D., & Blundell, J. E. (1996). Effects of short-term exercise on appetite responses in unrestrained females. European journal of clinical nutrition, 50(10), 663-667. |

| King 1997 | King, N. A., Lluch, A., Stubbs, R. J., & Blundell, J. E. (1997). High dose exercise does not increase hunger or energy intake in free living males. European journal of clinical nutrition, 51(7), 478-483. |

| Liddle 1995 | Liddle, R. A. (1995). Regulation of cholecystokinin secretion by intraluminal releasing factors. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 269(3), G319-G327. |

| Liu 1996 | Liu, C. D., Aloia, T., Adrian, T. E., Newton, T. R., Bilchik, A. J., Zinner, M. J., … & Mcfadden, D. W. (1996). Peptide YY: a potential proabsorptive hormone for the treatment of malabsorptive disorders. The American Surgeon, 62(3), 232-236. |

| Lluch 1998 | Lluch, A., King, N. A., & Blundell, J. E. (1998). Exercise in dietary restrained women: no effect on energy intake but change in hedonic ratings. European journal of clinical nutrition, 52(4), 300-307. |

| Martins 2007 | Martins, C., Morgan, L. M., Bloom, S. R., & Robertson, M. D. (2007). Effects of exercise on gut peptides, energy intake and appetite. Journal of Endocrinology, 193(2), 251-258. |

| Murphy 2006 | Murphy, K. G., & Bloom, S. R. (2006). Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature, 444(7121), 854-859. |

| O’Connor 1995 | O’connor, A. M., Johnston, C. F., Buchanan, K. D., Boreham, C., Trinick, T. R., & Riddoch, C. J. (1995). Circulating gastrointestinal hormone changes in marathon running. International journal of sports medicine, 16(05), 283-287. |

| Russek 1980 | Russek, M., & Racotta, R. (1980). A Possible Role of Adrenaline and Glucagon in the Control of Food Intake1. In Comparative Aspects of Neuroendocrine Control of Behavior (Vol. 6, pp. 120-137). Karger Publishers. |

| Ryu 2001 | Ryu, S., Choi, S. K., JoUNG, S. S., Suh, H., Cha, Y. S., Lee, S., & Lim, K. (2001). Caffeine as a lipolytic food component increases endurance performance in rats and athletes. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology, 47(2), 139-146. |

| Shillabeer 1987 | Shillabeer, G., & Davison, J. S. (1987). Proglumide, a cholecystokinin antagonist, increases gastric emptying in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 252(2), R353-R360. |

| Sliwowski 2001 | Sliwowski, Z., Lorens, K., Konturek, S. J., Bielanski, W., & Zoladz, J. A. (2001). Leptin, gastrointestinal and stress hormones in response to exercise in fasted or fed subjects and before or after blood donation. Journal of physiology and pharmacology, 52(1). |

| Sullivan 1984 | Sullivan, S. N., Champion, M. C., Christofides, N. D., Adrian, T. E., & Bloom, S. R. (1984). Gastrointestinal regulatory peptide responses in long-distance runners. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 12(7), 77-82. |

| Thompson 1988 | Thompson, D. A., Wolfe, L. A., & Eikelboom, R. (1988). Acute effects of exercise intensity on appetite in young men. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 20(3), 222-227. |

| Tsofliou 2003 | Tsofliou, F., Pitsiladis, Y. P., Malkova, D., Wallace, A. M., & Lean, M. E. J. (2003). Moderate physical activity permits acute coupling between serum leptin and appetite–satiety measures in obese women. International journal of obesity, 27(11), 1332-1339. |

| Vatansever-Ozen 2011 | Vatansever-Ozen, S., Tiryaki-Sonmez, G., Bugdayci, G., & Ozen, G. (2011). The effects of exercise on food intake and hunger: Relationship with acylated ghrelin and leptin. Journal of sports science & medicine, 10(2), 283. |

| Westerterp-Plantenga 1997 | Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S., Verwegen, C. R., IJedema, M. J., Wijckmans, N. E., & Saris, W. H. (1997). Acute effects of exercise or sauna on appetite in obese and nonobese men. Physiology & behavior, 62(6), 1345-1354. |

Leave a Reply