Intro

Imagine you had a long night. Fun, games, perhaps work kept you awake and forced you from the normal, to the late and into the early hours. When you finally hit the bed, the sweet embrace of sleep takes you almost instantly until your clock chimes in for a rude awakening. Then follows the grogginess of an incomplete night. You feel cold, have trouble to focus, call coffee your best friend, and just want to snuggle down on the couch with a book or a show in sight and your comfort food in hand.

These effects of sleep loss have their origin on a level deep inside our bodies; one where hormones flow and neurons fire. So push the blanket aside and lean in if you want to learn more about the how…

Sleep affects hunger.

A good night’s rest

The US. National Sleep Foundation recommends 7 to 9 hours of sleep every day for adults [Lloyd-Jones]. If we fall short of that mark, the risk for obesity and diabetes increases with soap opera esque drama [Spiegel 2005, Knutson 2008]. Speaking of drama, sleeping too long can also lead to similar detrimental effects [Chaput 2009].

The main reason why sleep deprivation pushes our BMI to the limits is that good sleep is a killer of hunger. Like oxygen, we only really notice it when it is missing, but when we do, boy does it make us scream for our preferred combination of fats, sugars and proteins [Schmid 2008, Pejovic 2010,Herzog 2013, Hoyos 2015].

A trip down circadian lane

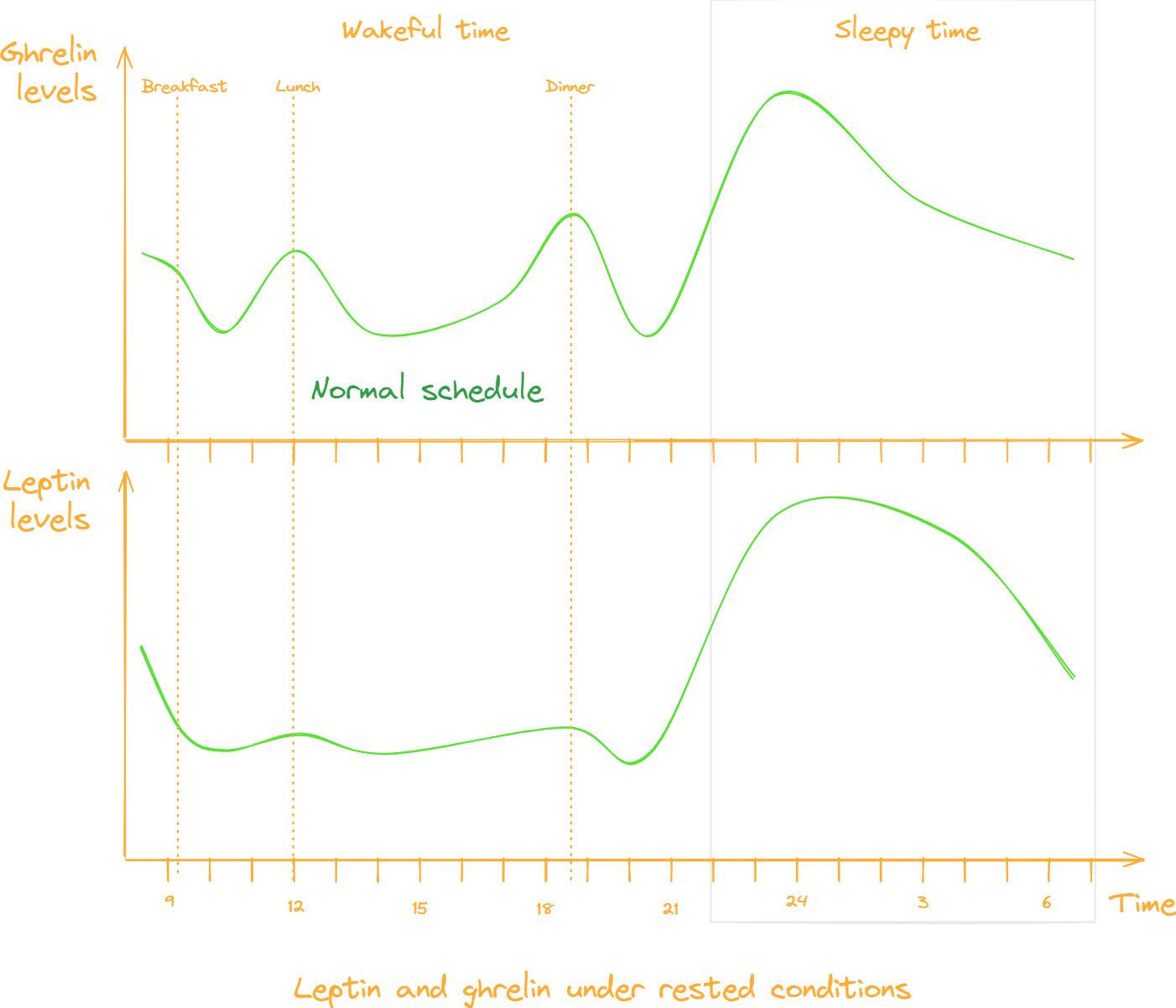

One of the reasons for that increase might be that our bodies are acutely attuned to the circadian rhythm. Like the ups and downs of stellar bodies, our internal hormone levels follow a day and night rhythm that best suits our lives [Rynders 2020].

Also the hunger hormone ghrelin and its counters leptin and PYY follow the internal clock [Mullington 2003, Rynders 2020]. Ghrelin does so to prepare us for food intake or the growth and regeneration-spur that we experience during sleep [Cummings 2001, Drazen 2006]. Depending on the time of day, PYY and leptin is either released to close feeding windows or nullify appetite, for example while we sleep [Mullington 2003, Rynders 2020].

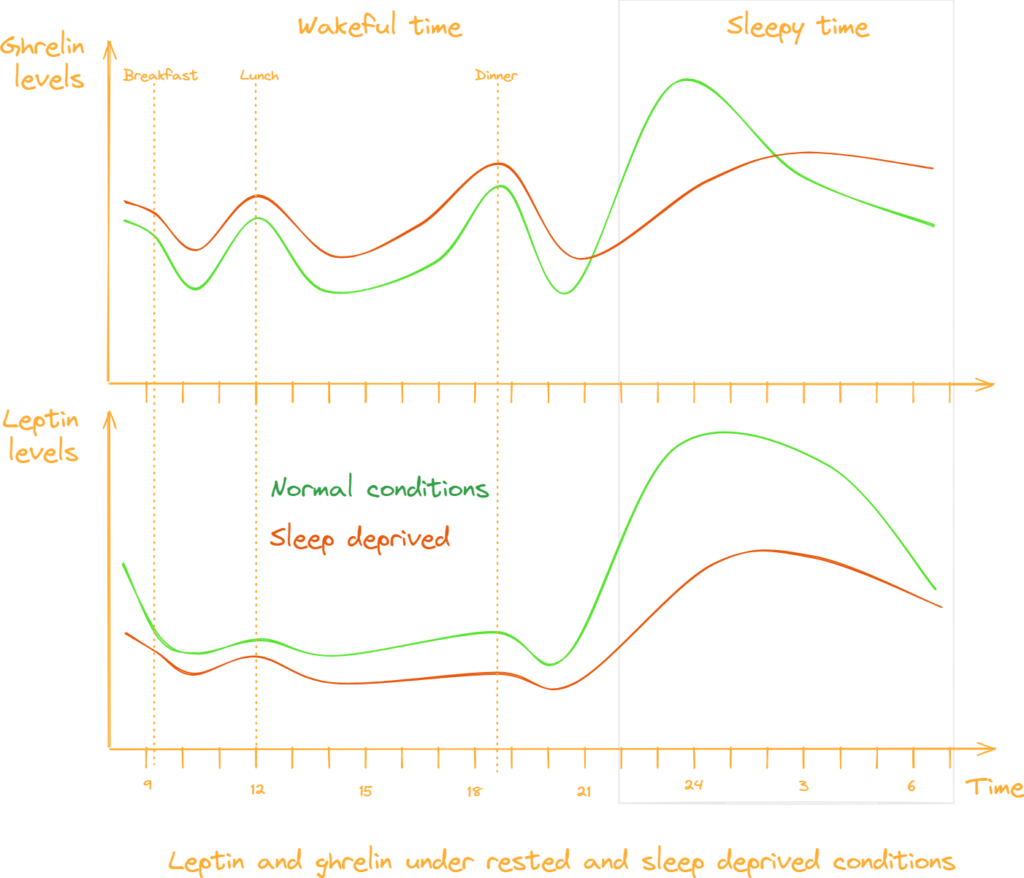

But all that changes when sleep deprivation hits us and lets slip the dogs of hunger.

A bad night’s rest

Ghrelin

Starting with ghrelin, lack of sleep releases the shackles a good night’s rest normally puts on it [Taheri 2004, Spiegel 2005, Schmid 2008]. Being the literal hunger hormone, ghrelin can’t but trigger the sweet sensation it is known for [Tschöp 2000, Nakazato 2001, Cummings 2004, Murphy 2006].

Leptin and PYY

And if that wasn’t enough its hormonal counters leptin and peptide YY, or PYY as the cool kids call it, get tied down instead [Mullington 2003, Taheri 2004, Schmid 2008, Magee 2009, Stern 2014].

Both leptin and PYY are anorexic (meaning appetite reducing) agents in the cold war of hunger. Without these two agents keeping up in the hormonal arms race, the feeling of hunger gets even stronger [Blundell 2001, Batterham 2002, Murphy 2006].

Insulin

And then there is insulin. The peptide is another victim of sleep deprivation’s rampage through our circadian rhythm. Like the others, insulin is also an important factor in the game of energy homeostasis and appetite [Pliquett 2006]. And normally that works fine.

In the case of low sleep quality or duration insulin effectiveness drops harder than the mic at a presidential correspondents’ dinner by increasing the body’s resistance to it [Donga 2010]. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why sleep deprivation not only promotes obesity but also type 2 diabetes [Spiegel 2005, Knutson 2008].

Outro

So the next time you have a chance to hit the sheets on time, remember the effect a late night can have on your body’s curvature. And if you find yourself in a situation where you just can’t sleep well, consider the other methods that help against hunger.

Go to bed to keep the bellies flat.

Sources

| Key | Citation |

|---|---|

| Batterham 2002 | Batterham, R. L., Cowley, M. A., Small, C. J., Herzog, H., Cohen, M. A., Dakin, C. L., … & Bloom, S. R. (2002). Gut hormone PYY3-36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature, 418(6898), 650-654. |

| Blundell 2001 | Blundell, J. E., Goodson, S., & Halford, J. C. G. (2001). Regulation of appetite: role of leptin in signalling systems for drive and satiety. International Journal of Obesity, 25(1), S29-S34. |

| Chaput 2009 | Chaput, J. P., Després, J. P., Bouchard, C., Astrup, A., & Tremblay, A. (2009). Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance: analyses of the Quebec Family Study. Sleep medicine, 10(8), 919-924. |

| Cummings 2001 | Cummings, D. E., Purnell, J. Q., Frayo, R. S., Schmidova, K., Wisse, B. E., & Weigle, D. S. (2001). A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes, 50(8), 1714-1719. |

| Cummings 2004 | Cummings, D. E., Frayo, R. S., Marmonier, C., Aubert, R., & Chapelot, D. (2004). Plasma ghrelin levels and hunger scores in humans initiating meals voluntarily without time-and food-related cues. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 287(2), E297-E304. |

| Donga 2010 | Donga, E., van Dijk, M., van Dijk, J. G., Biermasz, N. R., Lammers, G. J., van Kralingen, K. W., … & Romijn, J. A. (2010). A single night of partial sleep deprivation induces insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways in healthy subjects. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(6), 2963-2968. |

| Drazen 2006 | Drazen, D. L., Vahl, T. P., D’Alessio, D. A., Seeley, R. J., & Woods, S. C. (2006). Effects of a fixed meal pattern on ghrelin secretion: evidence for a learned response independent of nutrient status. Endocrinology, 147(1), 23-30. |

| Herzog 2013 | Herzog, N., Jauch-Chara, K., Hyzy, F., Richter, A., Friedrich, A., Benedict, C., & Oltmanns, K. M. (2013). Selective slow wave sleep but not rapid eye movement sleep suppression impairs morning glucose tolerance in healthy men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(10), 2075-2082. |

| Hoyos 2015 | Hoyos, C., Glozier, N., & Marshall, N. S. (2015). Recent evidence on worldwide trends on sleep duration. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 1, 195-204. |

| Knutson 2008 | Knutson, K. L., & Van Cauter, E. (2008). Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1129(1), 287-304. |

| Lloyd-Jones 2022 | Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Allen, N. B., Anderson, C. A., Black, T., Brewer, L. C., Foraker, R. E., … & American Heart Association. (2022). Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 146(5), e18-e43. |

| Magee 2009 | Magee, C. A., Huang, X. F., Iverson, D. C., & Caputi, P. (2009). Acute sleep restriction alters neuroendocrine hormones and appetite in healthy male adults. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 7, 125-127. |

| Mullington 2003 | Mullington, J. M., Chan, J. L., Van Dongen, H. P. A., Szuba, M. P., Samaras, J., Price, N. J., … & Mantzoros, C. S. (2003). Sleep loss reduces diurnal rhythm amplitude of leptin in healthy men. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 15(9), 851-854. |

| Murphy 2006 | Murphy, K. G., & Bloom, S. R. (2006). Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature, 444(7121), 854-859. |

| Nakazato 2001 | Nakazato, M., Murakami, N., Date, Y., Kojima, M., Matsuo, H., Kangawa, K., & Matsukura, S. (2001). A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature, 409(6817), 194-198. |

| Pejovic 2010 | Pejovic, S., Vgontzas, A. N., Basta, M., Tsaoussoglou, M., Zoumakis, E., Vgontzas, A., … & Chrousos, G. P. (2010). Leptin and hunger levels in young healthy adults after one night of sleep loss. Journal of sleep research, 19(4), 552-558. |

| Pliquett 2006 | Pliquett, R. U., Führer, D., Falk, S., Zysset, S., von Cramon, D. Y., & Stumvoll, M. (2006). The effects of insulin on the central nervous system-focus on appetite regulation. Hormone and metabolic Research, 38(07), 442-446. |

| Rynders 2020 | Rynders, C. A., Morton, S. J., Bessesen, D. H., Wright Jr, K. P., & Broussard, J. L. (2020). Circadian rhythm of substrate oxidation and hormonal regulators of energy balance. Obesity, 28, S104-S113. |

| Schmid 2008 | Schmid, S. M., Hallschmid, M., JAUCH‐CHARA, K. A. M. I. L. A., Born, J. A. N., & Schultes, B. (2008). A single night of sleep deprivation increases ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger in normal‐weight healthy men. Journal of sleep research, 17(3), 331-334. |

| Spiegel 2005 | Spiegel, K., Knutson, K., Leproult, R., Tasali, E., & Van Cauter, E. (2005). Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. Journal of applied physiology. |

| Stern 2014 | Stern, J. H., Grant, A. S., Thomson, C. A., Tinker, L., Hale, L., Brennan, K. M., … & Chen, Z. (2014). Short sleep duration is associated with decreased serum leptin, increased energy intake and decreased diet quality in postmenopausal women. Obesity, 22(5), E55-E61. |

| Taheri 2004 | Taheri, S., Lin, L., Austin, D., Young, T., & Mignot, E. (2004). Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS medicine, 1(3), e62. |

| Tschop 2000 | Tschop, M., Smiley, D. L., & Heiman, M. L. (2000). Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature, 407(6806), 908-913. |

Leave a Reply